Theft of livestock is a growing challenge for farmers along the Zimbabwe-Botswana border.

The traditional practice of allowing cattle, goats and sheep to roam free makes them easy targets for the rustlers.

Ms Bonang Ritiko keeps her animals penned but that has not deterred the crooks. She lost 20 head of cattle in one night during a raid on her village in Semolale in Botswana. Each night, the sound of barking dogs sends shivers down her spine. It is a signal of distress for her and other farmers who live at the mercy of cattle rustlers that Batswana allege come from Zimbabwe.

Like Ms Ritiko, most victims rely on their animals as their main source of income. Instead of depositing their money in banks, farming families often save their profits by investing in livestock.

The Batswana farmers in villages along the border are under serious threat from a new breed of highly organised cattle rustlers mainly from Shanyaugwe and John Deep villages in Gwanda South.

In June, Zimbabwe Republic Police arrested Nkosiyabo Gumbi (34) of Ngoma area in Gwanda for allegedly stealing 31 head of cattle from Botswana and driving the animals to his farm at Railway Block, West Nicholson.

“Although the police are doing their best, it appears that this is one war that they can’t win,” Ms Ritiko said.

On the opposite end, Zimbabwean farmers in villages which border with Botswana such as Nhwali, Mlambaphele, Guyu, Manama, Mankonkoni Rustlers gorge and villages in Bulilima District are not only facing challenges because of drought, but stock theft as well. They frequently lose large herds of cattle which “stray” to Botswana.

As a matter of policy, Botswana authorities shoot cattle that “stray” into their country. This has led to untold suffering for Zimbabwean farmers who allege that their cattle which would have “gone astray” will actually have been stolen by Botswana cattle rustlers.

In October last year, 112 head of cattle from Ward 19 in Mlambaphele were shot dead after they strayed into Botswana.

“This problem will drive us to our graves poorer. We need a permanent solution so that people don’t suffer losses,” said Ward 19 Councillor Tompson Makhalima.

Cattle rustling has transformed from petty theft by individuals to operations conducted by organised syndicates. It is a global phenomenon and, as well as being a regional problem, it also has transnational dimensions. In some Sadc countries, all indications point to a growing transnational organised criminal element to the issue.

Stock theft across the South African and Lesotho borders has also been ongoing for years. The stolen cattle from South Africa are hidden along the mountainous border and then moved into Lesotho where they are rebranded and sent back to South Africa then they are laundered through stock auctions.

South Africa police recorded 6 322 stock theft cases in KwaZulu-Natal during the 2017/2018 financial year, which was the highest provincial stock theft figure nationwide during that period.

Porous and poorly secured borders contribute to the problem. Large parts of the border fences are stolen, destroyed by elephants making monitoring long boundaries and mountainous terrain difficult for police. This creates many opportunities and trafficking routes for criminal networks to smuggle livestock.

Villagers around Beitbridge in Zimbabwe and across the Limpopo in South Africa have regularly complained that cattle rustlers steal their livestock and drive them across the Limpopo for slaughter.

Beitbridge and Musina communities are worried about growing illegal meat sales, which they say promote stock theft and poaching in areas around the two neighbouring towns. Last year, a Beitbridge magistrate sentenced to 14 years each in prison five cross-border cattle rustlers after they were caught at a cemetery in Musina skinning stolen cattle.

Matabeleland South provincial police spokesperson Chief Inspector Philisani Ndebele said:

“We suspect that these culprits take this meat and supply people or places that sell beef unofficially”.

The South African Police’s annual crime statistics report and surveys indicate that livestock farmers are mostly affected by stock theft in South Africa. The costs paid by these farmers to enhance security in the environs of their livestock roughly precede the financial planning meant for production.

Large-scale and small-scale livestock owners in South Africa, Zimbabwe, Botswana and Lesotho are victims of ongoing stock theft. For small-scale livestock owners, the theft of only a few animals can be financially devastating.

Livestock theft costs nations billions of dollars each year, damages the agricultural economy and negatively impacts food security.

The modus operandi of stock thieves has transformed from stealing for survival to looting for sale. If for survival, only a few animals are stolen or slaughtered, with the thieves taking what they can carry and leaving the carcasses behind.

Organised syndicates, plan their operations carefully and drive large herds of cattle in one night. In some instances, they collude with farm workers and farmers in neighbouring countries. The farm workers involved usually provide information about the farm to the criminals. Some desperate farmers help steal livestock from other farms so that they are spared during the infamous raids.

Zimbabwean cattle rustlers have developed a more sophisticated way of stealing cattle by driving their cattle to greener pastures in Botswana and altering existing brands and driving them to nearby Botswana farms. A rustler would settle down on a ranch with a small herd and lawfully registered brand that could easily be converted to that of a neighbouring ranch. He then catches the calves belonging to the unlucky farmer and brands or rebrands them as his own. He will then drive his cattle and the stolen herd back to Zimbabwe.

Early this year, Botswana farmers recovered a herd of 58 cattle and nine donkeys at Jani Farm in Gwanda. Some of the animals bore several brand marks stolen by Zimbabwean suspects.

Victims from Semolale, Bobonang, Gobojando and Mabolwe villages in Botswana’s Bobirwa District tracked the spoor of the stolen animals and were led to the Zimbabwe border. This led to the recovery of the animals.

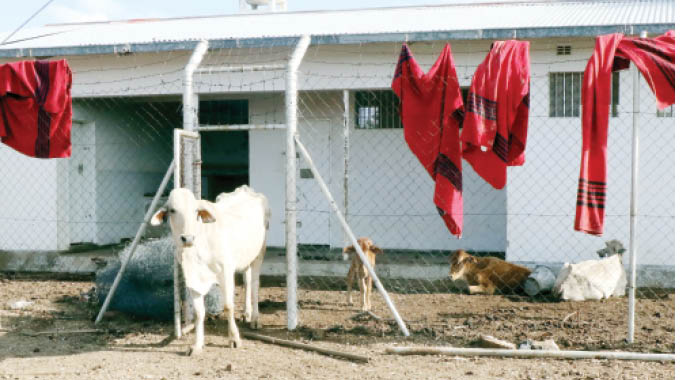

A Chronicle news crew recently saw hordes of unclaimed stolen cattle and goats from Botswana that are kept at Tuli Police Post near Mlambaphele border. The pens are also full of animal remains from cattle which die due to lack of food and water.

“All these are unclaimed stolen animals from Botswana. They were so many, but they die in numbers every day. We don’t have a budget to feed them,” said a police officer at the station.

Zimbabwe’s economic challenges have exacerbated the appetite for stealing cattle. Cattle rustling may also be a result of promising lives shattered, families betrayed, and revenge.

Bulelo Nyathi, a former herd boy in Botswana changed his career after his former employer handed him over to the police shortly before pay day so that he can be arrested and deported.

After deportation, he returned to Botswana and stole cattle from his former employer.

“Over time, I was convinced that I was invincible such that police devoted to tracking down cattle rustlers would never get me. I don’t feel sorry for my actions. Those people are ruthless, imagine; you expect to get paid, boom the next thing you are inside a gumba-kumba (prison truck).”

Local farmers complain that the justice system is not contributing enough to curb stock theft.

Ms Matsipi Dube of Nhwali blames the courts for delays in handling or resolving cases, high expenses, having a hard time getting access to legal counsel and understanding the law as some of the stumbling blocks.

She highlighted that lack of trust in police processes due to their inability to follow up on cases that are reported has resulted in the breakdown of the relationship between farmers and police.

“High costs, unfair treatment, corruption and lack of trust are just some of the reasons. We are struggling to get justice,” she said.

A prosecutor stationed in Matabeleland South said they receive many cases of stock theft but some of them are not prosecuted and even those that enter the court do not have enough evidence to warrant conviction.

“Many cases are brought here but they suffer stillbirths because many a time police do a shoddy job in investigating or the complainant’s evidence will be lacking merit,” he said.