KILLING THE HOLY GHOST

How the Musina-Makhado SEZ will parch the people of Zimbabwe

By Kevin Bloom• 19 November 2020

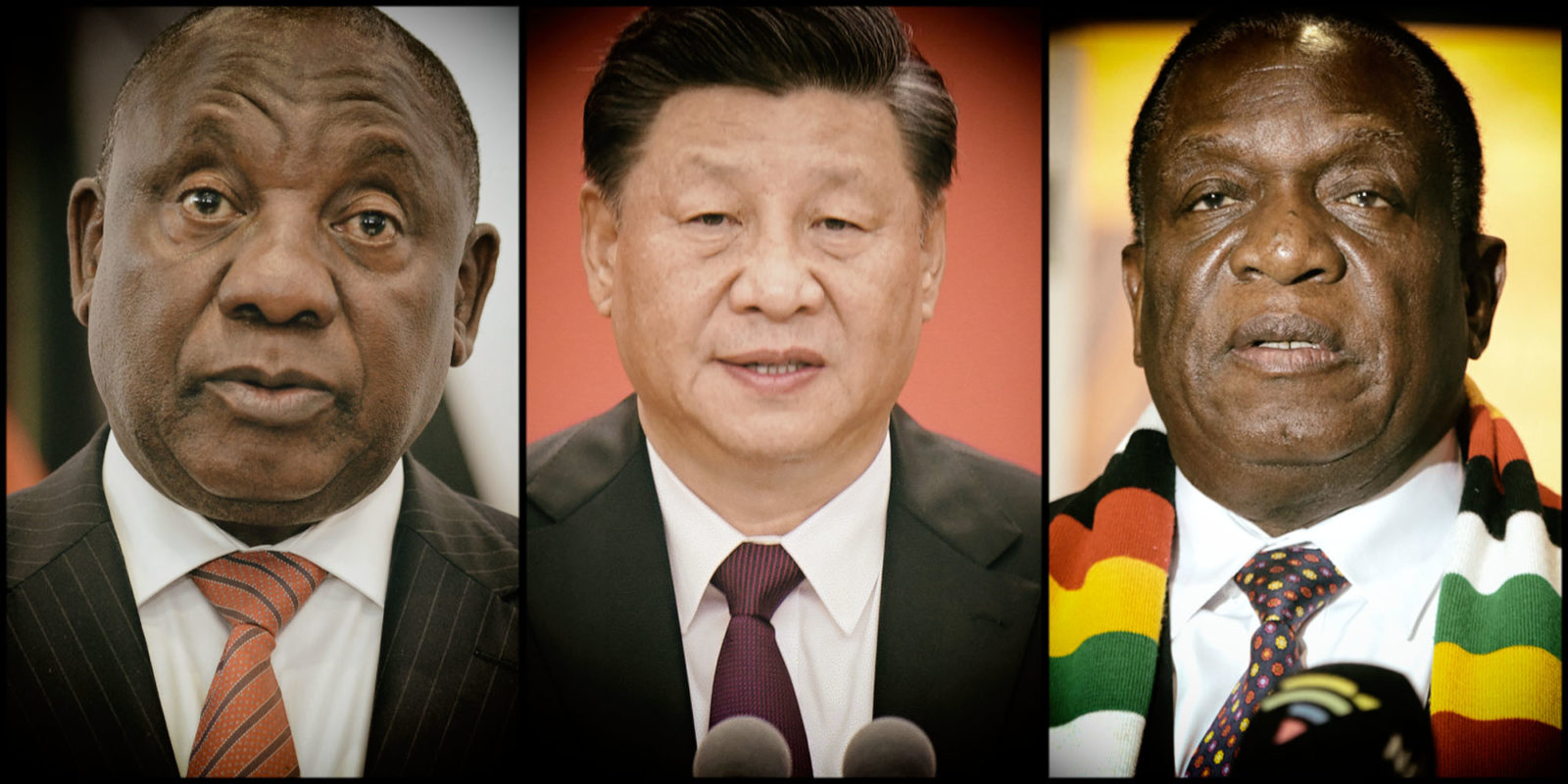

From left, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, Chinese President Xi Jinping and Zimbabwean President Emmerson Mnangagwa (Photos: Gallo Images / Deaan Vivier | EPA-EFE / Zhang Ling / Xinhua) | EPA-EFE / Aaron Ufumeli) Less

(For more in the Killing the Holy Ghost series, read Kevin Bloom’s two investigative features here and here, and Brandon Abdinor’s follow-up on the Draft Environmental Impact Assessment here.)

At the end of January 2014, when soldiers arrived on the banks of the Tokwe-Mukorsi Dam to relocate 20,000 Zimbabwean citizens to a displaced persons camp funded by international donors, they were met with stiff resistance. While pushback from rural villagers wasn’t new to these soldiers, what was new were the circumstances. The previous two months had seen record rainfall in the country’s south-eastern province of Masvingo, with measurements surpassing anything witnessed since the early 1970s, and while the authorities were blaming climate change for the flooding, the villagers were blaming the authorities themselves.

“When armed soldiers came to evict us,” an unnamed peasant farmer told Human Rights Watch a few months after the event, “we pleaded with them to open the tunnels in the dam wall and allow water to flow downstream of the dam, but they refused.”

But, reportedly, the commander of the army unit was resolute.

“President Mugabe directed that this dam should be constructed so that it contains water in it,” the commander informed the villagers, “and you ask us to let the water out? No. It is time for you to leave now. You will receive your compensation later, when government gets the money.”

Needless to say, the compensation would be nowhere near what these villagers had been promised. Back in 2011, when the resettlement programme for the Tokwe-Mukorsi Dam was put into effect, the Zimbabwean government had guaranteed that each displaced family would receive a 17-hectares plot of land and that each household would be compensated based on property evaluations. But by the end of 2013, when just 712 out of the total 6,393 families had been relocated — partly due to the resistance of families that wanted to be compensated before moving — the average size of the new plots was just four hectares. These families would nonetheless be far better off than those forced to relocate after the floods, who would receive only one hectare of land on which to eke out their livelihoods.

And so ultimately, after receiving $20-million in flood relief donor funding, the Zimbabwean government turned the record rainfall of the 2013/14 summer season into a tidy saving on the national budget. Not only that, but the flood victims, whose crops had been destroyed, stopped receiving aid from the World Food Programme in September 2014. The Masvingo provincial administrator’s office would eventually resort to a range of coercive tactics — including physical violence, denial of access to food and water, blocking of toilets and closure of the school and clinic — to shift the villagers onto the one-hectare plots.

“This situation contravenes every standard for dealing with internal displacement that has been put forward in the last 15 years,” noted Human Rights Watch in their report, before outlining the relevant clauses in the Zimbabwean, African Union and United Nations constitutions and conventions that had been breached.

As universally criminal as it was, though, the back-story of the Tokwe-Mukorsi Dam was destined to fade into history, consigned to the dustbin of Zimbabwean government abuses that had been ignored and forgotten by almost every member of the AU and SADC — including, most notably, Zimbabwe’s powerful neighbour to the south.

In September 2020, when the dam would be named on page 448 of the Draft Environmental Impact Assessment for the Musina-Makhado Special Economic Zone in the far north of South Africa, there would be no mention of the thousands of human beings whose lives had been uprooted. Instead, there would be an impassive acknowledgement of a different — and potentially more deadly — type of crisis.

“The projected water use for the SEZ is estimated at 80 million cubic metres per annum,” declared the document, in the section on “international” water implications. “This demand will create immense pressure on the local and cross‐border water resources as well as the regional transferring catchments relevant to this study area.”

Listed as one of four Zimbabwean dams earmarked for provision of water to the SEZ, all the document stated about Tokwe-Mukorsi was that it was a “newly completed dam located 250km from Beitbridge.” Aside from the human rights abuses that had been the direct result of its construction, the Draft EIA neglected to note why the dam had in fact been built.

Tokwe-Mukorsi, it turned out, was commissioned by the Zimbabwean government in the mid-1990s to provide irrigation and hydroelectricity to the sugar plantations and communal farmers in the semi-arid regions of Masvingo. As the largest inland dam in Zimbabwe, with an 89,2m-high dam wall, it had been beset by funding challenges and delays from the moment that Italian company Salini Impregilo JVC began construction in 1998 — the eventual cost overrun, when the dam was finally completed in 2015, was $165-million, more than double the initial budget.

The question, for anyone who knew anything about the Musina-Makhado SEZ, was whether the final price-tag of $300-million was about to be (literally) flushed down the tubes. Of course, while the compilers of the Draft EIA could not be altogether candid in response to such a question, there was no doubt that they expected it to be asked.

“Surface water in Zimbabwe accounts for 90% of the country’s supply,” the document explained. “Conversely, there is very limited knowledge on how much ground water there is and the potential to utilise this water for the country’s needs.”

In the very next sentence, the Draft EIA acknowledged the “impacts of climate change in these catchment areas” and its unavoidable consequences for “both surface and groundwater” in the country. Climate collapse, noted the compilers of the Draft EIA, “will affect Zimbabwe as well as the SEZ, which envisages to use water from Zimbabwe for day-to-day operations”.

For more than two decades now, exposing the secrets of Zimbabwe’s ruling party, Zanu-PF, has been a deadly dangerous business. Of the range of sources that Daily Maverick contacted for comment during the reporting for this story, there was not a single Zimbabwean citizen or resident who gave consent for his or her name to be used. One of our potential sources, who felt he owed us an explanation for his reticence, forwarded us a circular issued by the government of Zimbabwe in late October 2020.

“Information Minister Monica Mutsvangwa has told the media that Cabinet has approved [an] amendment that will criminalise the unauthorised communication or negotiation by private citizens with foreign governments,” the circular stated in its opening sentence.

Further down, there was confirmation that the impetus for the amendment had come from President Emmerson Mnangagwa himself:

“Harare is not happy with being called out for bad things at a time when it is trying to re-engage with the international community. President Mnangagwa, when he officially opened the 3rd Session of the 9th Parliament of Zimbabwe, highlighted his displeasure with NGOs and promised that [the] Bill was coming to alter their operations.”

Whether this had anything to do with the fact that Wally Schultz, the founder of the NGO Save Our Limpopo Valley Environment (SOLVE) and the most committed and effective anti-SEZ activist in South Africa, received a barrage of “join the campaign” requests from Zimbabwe in late October was impossible to confirm. Schultz, who would tragically suffer a stroke on Friday, 30 October — a massive blow by all accounts to the conservation movement in Limpopo — had told Daily Maverick the day before that he was treating all such requests with the utmost circumspection.

“They smell like Zim government snoops to me,” he’d said, “I’ve refused more than half of them.”

Legitimate or not, what Schultz, like the rest of the growing cabal of anti-SEZ activists knew, was that our own government was dead set on going ahead with the R145-billion project. In late August 2020, the SEZ’s CEO Lehlogonolo Masoga published an article in which the initiative was presented as a fait accompli — its “locational advantage” close to the Beitbridge border with Zimbabwe, he suggested, would be one of its greatest benefits, setting it up as a potential “inland intermodal terminal”.

Whatever that meant, it was clear that the major north-south trucking route that connected the SADC bloc to South Africa via Zimbabwe had always been a core impetus for the SEZ. As for the impact that the project’s various industrial plants — “coal power, coke, ferrochrome, ferromanganese, pig iron, carbon steel, stainless steel, lime, silicon-manganese, metal silicon and calcium carbide” — would have on the irreplaceable biodiversity of the Limpopo River Valley, Masoga would only offer that “specialist studies” on pollution and climate change had been commissioned.

“With regard to water scarcity,” he added, “efforts are being made to avoid tapping into the already stressed water resources by exploring various innovative engineering options, including cross-border water-transfer schemes.”

On this point, Masoga seemed to be taking his cue from Lindiwe Sisulu, South Africa’s human settlements, water and sanitation minister, who in June 2020 had responded to questions in Parliament regarding the water resource implications of the SEZ.

“The Zimbabwe-South Africa Joint Water Commission is about to initiate planning studies to investigate water resource development options in Zimbabwe for the benefit of both countries,” she’d said. “Since the signing of the agreement, the technical teams of both countries have been continuously meeting to initiate the joint studies and to make updates on water related issues of mutual interest to both parties.”

As far as Daily Maverick could ascertain, the “agreement” to which Sisulu was referring was nowhere in the public domain. Although the local environmental NGO Earthlife Africa had submitted a request under the Promotion of Access to Information Act (Paia), at the time of this writing nothing had been forthcoming. Neither had Schultz, for all his efforts, managed to get sight of the document.

That the agreement existed was beyond dispute, however, especially given the report that had been commissioned by the Department of Water and Sanitation in 2016, entitled “Limpopo Water Management Area North Reconciliation Strategy”. Here, the legislation, treaties and policy documents that “have a bearing on international obligations regarding water allocations out of the shared Limpopo River” were enumerated. But since the report referred throughout its 140 pages to the SEZ and Zimbabwe, it was implicit that these legal instruments would have governed the negotiations of the Zimbabwe-South Africa Joint Water Commission too.

Among the instruments mentioned were the South African Constitution, the National Water Act of 1998 and the Convention on the Law of the Non-navigational Uses of International Watercourses Adopted by the General Assembly of the UN on 21 May 1997. Also featured were the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants and the SADC Revised Protocol on Shared Water Courses.

“The character of these legislation, treaties and policy documents promotes inter alia the sustainable, equitable and reasonable utilisation of shared watercourse systems and avoiding causing any negative impact to the neighbouring state,” noted the report.

How that could be reconciled with the report’s stated intention to divert 30 million cubic metres a year from Zimbabwe’s Zhovhe Dam to the Musina-Makhado SEZ was anyone’s guess.

In September 2019, the Zimbabwean company Zhovhe Estate announced that in the previous three years it had invested more than $10-million on irrigation infrastructure development, livestock production and fisheries “to complement government efforts towards food and nutrition security.” At the time, according to the World Food Programme, the country was in the grip of its worst food crisis in a decade, with more than half the population — 7.7 million people — lacking reliable access to affordable nutrition. Not only was acute malnutrition up almost 50% against 2018, but undependable rains were hitting subsistence farmers the hardest, since maize — their staple crop — had always been the most water-intensive.

Zhovhe Estate was of course named for the dam upon which its business model depended, and as “the biggest supplier of flour, mealie meal and fish to communities in Matabeleland region” it was in full alignment with the intended purpose of the infrastructure. Zhovhe Dam had been completed in 1995, with a carrying capacity of 133 million cubic metres — at its opening, according to Daily Maverick’s sources, Zimbabwe’s former agriculture minister Kumbirai Kangai announced that 60% of the dam’s capacity had been earmarked for commercial agribusiness and 40% for subsistence farming.

Although Daily Maverick failed to get hold of Zhovhe Estate’s CEO for comment, one of our sources did say this:

“That dam is the lifeblood of the area. Without it, it’s pretty much death.”

Because, ultimately, even the compilers of the Draft EIA had to admit that none of this was a great idea. In order to understand the full impact of climate collapse on Zimbabwe’s water resources, their model looked at worst- and best-case carbon emission scenarios — and either way, their equations added up to disaster.

But the manner in which the Musina-Makhado SEZ would affect the bustling border town of Beitbridge, with its population of 43,000, was another question entirely. As the main supplier of water to the town, the Zhovhe Dam had for more than two decades been core to its existence — so much so that Dr Aron Maboyi, Zanu-PF politburo member, had in January 2020 berated the citizens of Beitbridge for squandering their good fortune.

“Dr Maboyi,” according to the government-backed Chronicle newspaper, “said Beitbridge people had only themselves to blame if they do not make use of important natural resources in their area to turn around their lives.”

The good doctor, it transpired, was making such comments in the context of the prevailing drought, and although the dam wasn’t exactly a “natural” resource, it was clearly the nub of the Chronicle’s propaganda effort. Zhovhe Dam “is at a high place,” added Dr Maboyi, “and can distribute water to most places here through gravitation.”

Which was exactly the term employed by the compilers of the all-important Draft EIA for the Musina-Makhado SEZ. “Raw water from Zhove via gravity for pick up at Beitbridge,” the document stated in shorthand on page 448, after noting that “potable water from Beitbridge water treatment plant” could also be used.

The most concerning thing about the place of the Zhovhe Dam in the South African government’s plans for the SEZ, however, was the fact that it was marked as “short term” — meaning, whatever was going on in the closed-door meetings of the Zimbabwe-South Africa Joint Water Commission, the dam was more than likely top of the agenda.

As for the remaining two Zimbabwean dams in the South African government’s sights (Tokwe-Mukorsi, as per the Draft EIA, was slated for the medium term), these were set down for use in the far future, mainly because construction on both had yet to begin. The Thuli-Moswa Dam upstream of Zhovhe in the Mzingwane River catchment, with its capacity of 420 million cubic metres, and the Kondo-Chitowe Dam in the Save River catchment, which at a price-tag of $3.7 billion would overtake Tokwe-Mukorsi as the largest in the country, were no doubt where the joint water commission was hedging its climate change bets.

Because, ultimately, even the compilers of the Draft EIA had to admit that none of this was a great idea. In order to understand the full impact of climate collapse on Zimbabwe’s water resources, their model looked at worst- and best-case carbon emission scenarios — and either way, their equations added up to disaster.

“Runde and Mzingwane water catchment areas, which are sources of short‐ and medium‐term water for the SEZ, will be affected the most,” the Draft EIA explained, with reference to the Zhovhe and Tokwe-Mukorsi dams.

“It is predicted the mean annual precipitation will decline in the region of between 12% for higher mitigation emission scenarios and 16% for lower emission mitigation scenarios by 2050. This significant uncertainty related to water supply poses a major risk to the SEZ.”

So, again, was the project really going ahead? The question could perhaps best be answered by what the South African government had chosen to overlook.

In early April 2020, Daily Maverick ran an investigative feature that outlined the history behind the deal, highlighting the fact that the Department of Trade and Industry had on 15 September 2017 awarded the SEZ operator permit to a Chinese-owned company called the South African Energy Metallurgical Base (Pty) Ltd. As it turned out, the Zimbabwean police “through Interpol” had issued an arrest warrant for the company’s chairman, Mr Ning Yat Hoi, in the very same month that the permit was granted.

Ning denied the allegation that he had defrauded a pair of Zimbabwean mining companies to the tune of $2.76-million, and informed Daily Maverick that if we wanted to know the truth we would find it in accounting firm Ernst and Young’s Zimbabwe office. Unable to get to Harare due to Covid-19 travel restrictions, we couldn’t proceed any further. But then if such evidence existed, it had never been made available to the South African public—the DTI, despite all the questions that the media had thrown at them regarding Ning, had never once acknowledged the problem.

The suggestion, then, was that the Musina-Makhado SEZ had been driven from the start by the agendas of top-tier geopolitics. With nine Chinese companies having pledged R145-billion to the project, it was couched from the outset in the language of foreign direct investment and jobs. Behind that, however, was the place of the People’s Republic of China in Africa — as Daily Maverick argued in November 2018, Beijing’s “Belt and Road Initiative,” the largest development plan of the modern era, had always been poised to push Africa’s fragile ecosystems over the edge.

Could President Cyril Ramaphosa or President Emmerson Mnangagwa stand up to Premier Xi Jinping? Would they even want to? If the answer was no, and by all accounts it was, the rural citizens of Zimbabwe were about to lose a lot of the water in their dams. DM/OBP